First, God cursed the serpent. Then, he killed with it. Now it’s a symbol of health.

From Genesis, Numbers and Showtime’s Billions, a story of second chances.

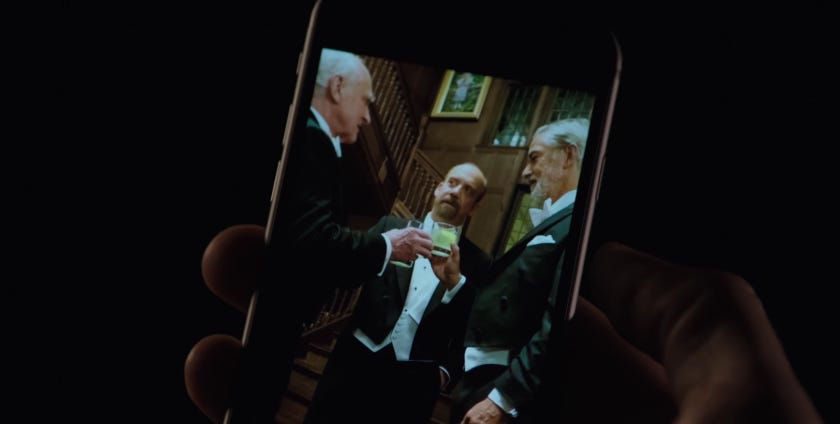

For Bobby Axelrod, there was no coming back from snitching. Or so he thought.

When Axe, hedge fund owner and protagonist of Showtime’s Billions, crosses paths with underling-turned snitch-turned caterer Dan Margolis while walking into a meeting, he barely makes time for a hello.

But then Axe went inside and met with “Black” Jack Foley, the New York power broker whose magic fingers had killed his casino deal.

Instead of a windfall, Axelrod was out money. He had to talk to the man who did it. He had to learn why it happened, and who sent him.

For God, there was no coming back from speaking against his wishes. Or so he thought.

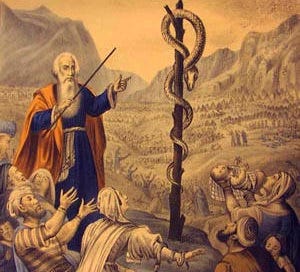

After “The Fall” in Genesis 3, after a serpent talks two humans made in God’s image into breaking the one and only rule they’d been given — don’t eat from that tree — God curses the serpent.

“Because you have done this, cursed are you above all the livestock and the wild animals. You will crawl on your belly and you will eat down at all the days of your life.

And I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will crush your head, and you will strike his heel.” — Genesis 3:14-15

That’s it for the serpent, for a long time. He slithers away, silently. Never again will he speak against God.

But the serpent is still part of God’s plan. He’s still useful.

Often we use our condition, at a point in time, as proof of God’s faithfulness, or lack thereof. We haven’t zoomed out, because we can’t. We can’t possibly know what we’re being prepared for.

That’s where faith comes in. It’s the belief that this step in the journey is important, as it will lead to the next.

Martin Luther King Jr. described faith as taking steps when you can’t see the whole staircase. But it’s more like running stairs and not knowing when the coach will blow the whistle.

The very traits that came from the serpent’s curse — the belly-crawling, the dust-eating, the enmity between it and mankind — are what makes it dangerous, in a different way.

The serpent’s cunning is gone, replaced by fangs. His words are no longer poisonous, but his venom is.

Axe leaves Foley’s house in a huff. He got nowhere.

He sees Margolis again, and finds a use for him. He’s found the one offense worse than snitching: throwing rocks at the castle.

Axe gives Margolis an opportunity. Take pictures from Foley’s party tonight, and I’ll pay off your house.

There’s no coming back to Axe Capital, so “I have to use you for what you are now,” Axelrod tells Margolis.

The offer is accepted. The pictures prove that Axelrod’s nemesis, Chuck Rhoades — U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York — is close with Foley. Not the answer Axelrod wanted. But the answer.

In Numbers 21, we see the serpent re-emerge and be used by God “for what he is now.”

The Israelites are still in exodus mode, between Egypt and the Promised Land. Food and water are a constant worry.

More than a few times, the Israelites accuse Moses of dragging them from a life of material comfort in Egypt “to die in the desert.” The Israelites, remember, went to Egypt to join brother Joseph and thrive in a global famine.

Things soured with the Egyptians after Joseph died, not surprisingly. But, after leaving Egypt, Israel’s hunger returned.

They were promised a new home, a land of milk and honey. But some Israelites felt Egypt fit that description better.

Even the manna, dropped off by quails to the Israelites since Exodus 16, didn’t hit like it used to.

“(Israel) spoke against God and against Moses and said, ‘Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the desert?” reads Numbers 21:5. “There is no bread! There is no water! And we detest this miserable food!”

In Numbers, God had heard a “stiff-necked people” whine for several books of the Bible now. He’s annoyed with it. Not just because whining is annoying, but because it shows a lack of faith. Israel’s constant refrain is, what have you done for me lately?

God then calls on the first character to be punished for their words, the serpent, to help him punish the latest, the Israelites.

Numbers 21:6 tells that God “sent venomous snakes among them; they bit the people and many Israelites died.”

Sounding quite like Pharaoh in Exodus, when overwhelmed by plagues and locusts, Israel apologizes to Moses, and asks God to rescind his punishment.

“We sinned when we spoke against the Lord and against you,” the Israelites say in Numbers 21:7. “Pray that the Lord will take the snakes away from us.”

Moses prays, and the snakes go away.

But a man in his position can’t spend time praying away snake bites. God tells Moses to make a snake and put it on a pole, so that “anyone who is bitten can look at it and live.”

“Then when anyone was bitten by a snake and looked at the bronze snake, he lived,” reads Numbers 21:8.

What reads like ancient superstition lives on today in most every health system on Earth. Against all odds, the serpent has endured.

In God’s good graces, the snake was turned from a taker of eternal life, to a killer, to a healer.

If it were anyone else but God who ordered the bronze snake created, they’d be guilty of idolatry. Instead, we have a story of second chances, tucked into an Old Testament full of harsh judgments.

If God can reform the image of the once-disloyal serpent, what can he do with you?